By Valerie Brown

Valerie Brown is an independent journalist based in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. She has written about environmental health, climate, radiation, energy and other issues for numerous publications including Miller-McCune Magazine, High Country News, SELF, and Environmental Health Perspectives. In 2009 she was awarded first prize for explanatory print journalism by the Society of Environmental Journalists for her article “Environment Becomes Heredity” in Miller-McCune Magazine.

As the world gapes mesmerized at the nuclear disaster unfolding in Japan, those not at risk of exposure to the radiation bless their good luck and wonder what it must feel like to be the unlucky ones – the ones who can’t escape that invisible blanket of fear.

Let me tell you what it feels like.

On a spring day in 1975, the first words I heard as I rose through the fog of anesthetic were “it was malignant.” I was twenty-four years old. A couple of months earlier during a routine physical my doctor had found a mass on my thyroid gland. X-rays and ultrasound had failed to clarify whether the mass was a fluid-filled cyst or a solid tumor. The only choice was surgery. The tissue analysis during the operation confirmed a diagnosis of thyroid cancer. The surgeon removed one lobe and the isthmus of the barbell-shaped gland at the base of my neck. I was informed that I’d take thyroid hormone for the rest of my life because if my own remnant gland were to start functioning again, it might grow itself another cancer. And so I have taken the little pill every morning for thirty-six years. It took a long time for the screaming red scar around my neck – the kind that was later dubbed the “Chernobyl necklace” – to fade.

On a spring day in 1975, the first words I heard as I rose through the fog of anesthetic were “it was malignant.” I was twenty-four years old. A couple of months earlier during a routine physical my doctor had found a mass on my thyroid gland. X-rays and ultrasound had failed to clarify whether the mass was a fluid-filled cyst or a solid tumor. The only choice was surgery. The tissue analysis during the operation confirmed a diagnosis of thyroid cancer. The surgeon removed one lobe and the isthmus of the barbell-shaped gland at the base of my neck. I was informed that I’d take thyroid hormone for the rest of my life because if my own remnant gland were to start functioning again, it might grow itself another cancer. And so I have taken the little pill every morning for thirty-six years. It took a long time for the screaming red scar around my neck – the kind that was later dubbed the “Chernobyl necklace” – to fade.

I was very lucky. I can say that now, after so many years without a recurrence. But it has been thirty-six years of ever-present fear and not a few physical problems, along with an increasing sense of outrage, as the likely cause of my trauma has gradually been revealed to me.

At the time, “Why me?” was uppermost on my mind.

“We don’t know what causes it,” my doctor told me in a casual tone. “But a lot of young women get thyroid cancer.”

Although I tried to put it behind me, I developed a form of post-traumatic stress disorder. I became terrified of my body. Every blemish triggered anxiety about new tumors. Every routine screening was a nightmare. I endured a string of significant but non-fatal health problems involving several more surgeries and biopsies. One time I asked a doctor whether having had cancer once meant I’d paid my dues. He laughed, saying the opposite was true: One cancer increases the odds of getting another cancer, or of the original cancer spreading to other organs. Paying your dues early doesn’t get you a free pass later.

I can’t say I handled the experience well. As a young baby boomer I was already immersed in the nihilism triggered by the long shadow of the Cold War and the white-hot rage of the Vietnam War – whoopee, we’re all gonna die! And yet at the same time, because I was so young, I didn’t know anybody else who was even sick, let alone a cancer victim. Back then there were no cancer support groups, no proud survivors wearing colorful scarves during their chemotherapy phases. No doctor suggested to me that I might find a little counseling helpful.

I can’t say I handled the experience well. As a young baby boomer I was already immersed in the nihilism triggered by the long shadow of the Cold War and the white-hot rage of the Vietnam War – whoopee, we’re all gonna die! And yet at the same time, because I was so young, I didn’t know anybody else who was even sick, let alone a cancer victim. Back then there were no cancer support groups, no proud survivors wearing colorful scarves during their chemotherapy phases. No doctor suggested to me that I might find a little counseling helpful.

As I wandered through my twenties and early thirties, I kept an ear cocked for any information I might come across about what causes thyroid cancer. In 1986 – the Chernobyl year – I learned that the link between exposure to ionizing radiation and thyroid cancer was far and away the strongest of all the disease’s possible causes. So I began pondering how I might have been exposed to such radiation.

That’s when things really started to get ugly. I found an embarrassment of riches. I had grown up in a kind of Nuclear Triangle. Ninety miles north of my home town of Pocatello, Idaho, the Idaho National Laboratory squats in the desert. When I was six months old, the first nuclear-generated electricity in the world was produced there. The site has the highest concentration of reactors in the world – fifty-two (most now mothballed). Although no one admits to any large airborne releases of radiation, at least 11 billion gallons of radioactive waste were injected into the Snake River aquifer between 1953 and 1984.

A few hundred miles to the northwest, a similar cluster of deceptively bland buildings crouches on the Columbia River basalt at Hanford, Washington. During production of the plutonium used in some of the world’s first nuclear weapons, millions of curies of I-131 were released to the air at Hanford.

The government knew at least as early as the mid-1940s that potassium iodide was protective against I-131 absorption by the thyroid. The government neglected to tell the public this, or notify downwinders either ahead of time or afterward about any releases of I-131 from any of its facilities. In fact, the government rarely acknowledged public risk from radiation released at any of its weapons facilities around the country. When forced to, the feds insisted there was no danger. Just like the Japanese and U.S. governments are doing today.

I thought the Idaho and Washington sites were the most likely places where I could have intersected with a cloud of radioactive iodine, because my family had taken many vacations either in Idaho’s central mountains (which we reached by driving through the Idaho nuclear reservation past signs warning of arrest or worse if a motorist should stop for any reason), or in trips down the Columbia River highway to visit relatives in Portland.

I thought the Idaho and Washington sites were the most likely places where I could have intersected with a cloud of radioactive iodine, because my family had taken many vacations either in Idaho’s central mountains (which we reached by driving through the Idaho nuclear reservation past signs warning of arrest or worse if a motorist should stop for any reason), or in trips down the Columbia River highway to visit relatives in Portland.

But in fact the most likely source of that I-131 lay to the southwest: the Nevada Test Site near Las Vegas. I knew almost nothing about the NTS, but by 1997 I had begun to learn. That year the National Cancer Institute published a map of where the many clouds of I-131 had traveled from the 925 nuclear tests in Nevada between 1951 and 1963. While my county was not the hardest hit, it had definitely been hit multiple times. The National Cancer Institute exposure calculator says I probably received a total of 10 rads of I-131 from 47 separate tests between 1951 and 1966. A USEPA table of health effects indicates changes in blood chemistry appear at 5-10 rad/rem, but this is still considered a relatively low dose, not expected to cause acute symptoms of radiation sickness.

As I gleaned more information my resentment continued to smolder. Then in about 2004, an Idaho native named Sheri Garman decided enough was enough. Dying of thyroid cancer that had spread to her breast and liver, Sheri spent the last year or so of her life making Idahoans aware of how much fallout the state had received and making Idaho politicians push for compensation for those of their citizens whose lives had been lost, shortened, or made a living hell by federal policy.

Four of the five counties in the nation hit hardest with I-131 are in Idaho (the top county is in Montana). Sheri Garman’s home town of Emmett, an idyllic dairy-and-cherry heartland gem near Boise, got the most I-131 in the state. Most Idahoans had no idea they’d been exposed to so much radiation, but as the penny dropped, they rallied around Sheri and demanded the chance to tell their own stories of pain, heartbreak, and financial ruin by medical bills.

Rage really churned up when it emerged that the NTS decision makers had routinely waited to detonate their bomb tests until the wind was blowing exactly toward Idaho. One government document characterizes people living under that plume trajectory as “a low-use segment of the population.” (This was well known to Utah downwinders, who’d understood their experience far earlier than Idahoans did.)

Sheri Garman lived just long enough to get a bill introduced that would make Idahoans eligible under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act and to see her daughter graduate from high school. Seven years later, Idahoans are still waiting as the bill languishes in committee. Baby boomer downwinders know that politicians and policymakers are playing a waiting game: as soon as we all die off, the pressure on them to act will evaporate – unless, of course, a new collision of natural forces and human error creates a new generation of downwinders. Which is starting to look more likely as of this writing.

Sheri Garman lived just long enough to get a bill introduced that would make Idahoans eligible under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act and to see her daughter graduate from high school. Seven years later, Idahoans are still waiting as the bill languishes in committee. Baby boomer downwinders know that politicians and policymakers are playing a waiting game: as soon as we all die off, the pressure on them to act will evaporate – unless, of course, a new collision of natural forces and human error creates a new generation of downwinders. Which is starting to look more likely as of this writing.

Throughout this long journey I have struggled to understand the nature of radiation risk. Between the discovery of the growth and the moment when I regained consciousness after my thyroidectomy, my ears had been filled with the voices of doctors thinking they offered comfort when they assured me that “99% of these tumors are benign.”

For the person falling into that last 1%, the world’s underpinnings shift. Instead of a probabilistic world where we are comfortable making decisions according to, say, the odds of thunderstorms ruining a picnic, we are thrust into binary hell, where the choices and chances are only two: win or lose, white or black, benign or malignant.

Yet the innards of atoms also follow probabilistic patterns. At that scale, cause and effect cannot be linked in straight lines. No one can say just which subatomic particle will be ejected from which atom with what amount of energy, or who will absorb how many of those particles, or which of a person’s cells will be hit by them, or whose immune system will be unable to repair the damage done by these tiny loose cannons rocketing through their tissues. “Experts” generally say things like, “There might be X number of additional cancers” in a particular exposed population, but they cannot say who will get those cancers – a handy out when it comes to apportioning right and wrong and assigning moral accountability. The problem is converted from a concrete one affecting real human beings to an abstract one affecting nobody in particular. Most of us are fine with that sort of risk as long as it’s not us on the operating table.

As the terrible news from Japan keeps breaking in ever-worsening waves, and as I sample the boiling Twittersphere, the pontificating of experts, and worst of all the drivel spouted by government authorities, I get angry all over again. Everywhere I turn, I hear that unless radiation levels get improbably high, nobody will get sick, as if acute radiation sickness is the only consequence of exposure. Read my lips: There is no such thing as a guaranteed “safe” level of exposure to ionizing radiation. Certainly, distance from the source and dilution in the atmosphere lowers exposure risk. Sure, you can swallow some potassium iodide to prevent your thyroid gland from absorbing I-131, although it won’t protect you from the cesium-137 or the strontium-90 or the plutonium.

The official focus on high short-term doses is deceptive. Emerging science suggests that low doses of radiation exposure can have numerous long-term effects, possibly passed from one generation to the next. And almost all the discussion about – and the scientific research on – radiation exposure focuses on cancers. There are certainly many cancers that radiation can induce in addition to thyroid cancer, from breast and prostate cancer to various leukemias. These cancers are thought to result from energetic particles striking DNA, breaking strands, and interfering with gene replication. Faulty genes lead to faulty cells, is the thinking. But there may also be epigenetic effects – that is, changes in the way normal genes are organized and allowed to function – and these may result in disorders other than cancer, such as thyroid diseases, autoimmune problems, and hormones gone haywire.

The official focus on high short-term doses is deceptive. Emerging science suggests that low doses of radiation exposure can have numerous long-term effects, possibly passed from one generation to the next. And almost all the discussion about – and the scientific research on – radiation exposure focuses on cancers. There are certainly many cancers that radiation can induce in addition to thyroid cancer, from breast and prostate cancer to various leukemias. These cancers are thought to result from energetic particles striking DNA, breaking strands, and interfering with gene replication. Faulty genes lead to faulty cells, is the thinking. But there may also be epigenetic effects – that is, changes in the way normal genes are organized and allowed to function – and these may result in disorders other than cancer, such as thyroid diseases, autoimmune problems, and hormones gone haywire.

To make matters worse, how old you are when you’re exposed makes a big difference too. Prenatal insults including chemical and radiation exposure can create epigenetic patterns of gene expression that will stay with you forever, even if your actual genes are undamaged. And it can take 50 or more years for the timer set in the womb to trip the fuse and trigger a full-blown disease.

In a 2009 review article, Canadian researchers Carmel Mothersill and Colin Seymour of McMaster University nicely expressed the emerging state of knowledge about the effects of low-level radiation exposure:

“Our understanding of the biological effects of low dose exposure has undergone a major paradigm shift….[W]e understand, at least in part, some of the mechanisms which drive low dose effects and which perpetuate these not only in the exposed organism but also in its progeny and in certain cases, its kin. This means that previously held views about safe doses or lack of harmful effects cannot be sustained.”

I’ve spent a lot of time in that miserable state of anxiety where I can almost feel each invisible ray invading my body, leaving me paralyzed by fear. This is not a useful condition to be in. I have learned to resist it, in large part because every minute I spend terrorized is another minute of my life paid over to the patronizing hubris of the military-industrial complex.

On the bright side, it’s true that you’re not necessarily totally doomed if you’ve been exposed to some ionizing radiation. Your body probably does have defenses. There are far better treatments for cancers now than ever before, and survival rates are improving. As one doctor said to me, “If you’ve got to have cancer, thyroid cancer is the one to get” because it grows slowly and is unlikely to metastasize before it’s caught. Many other cancers are also treatable. But no one can say who will dodge the glowing bullet, and who will not. Nor do the cavalier shrugs of politicians and pundits take into account the inevitable emotional distress, the life disruption, and the financial strain that accompany any cancer diagnosis, even one with a cheerful prognosis.

The NTS bomb-makers let their fallout descend upon the “low-use segment of the population” because there would have been too much squawking had they let it rain on Los Angeles instead. We hear a similar concern for Tokyo now. Probably this worry derives from the difference in population density between urban and rural or small town areas, but there is a tacit implication that non-urban dwellers are more expendable than urban dwellers. How large – or rich, or well-educated, or “citified” – must a sacrifice population be for the sacrifice to be unacceptable?

The NTS bomb-makers let their fallout descend upon the “low-use segment of the population” because there would have been too much squawking had they let it rain on Los Angeles instead. We hear a similar concern for Tokyo now. Probably this worry derives from the difference in population density between urban and rural or small town areas, but there is a tacit implication that non-urban dwellers are more expendable than urban dwellers. How large – or rich, or well-educated, or “citified” – must a sacrifice population be for the sacrifice to be unacceptable?

In the current crisis, the constant emphasis in official pronouncements and media commentary on the very low likelihood of high enough exposures to make a person immediately sick obscures the fact that as long as we use nuclear technologies, we cannot prevent radiation exposure, and that some people are going to get sick from our use of them. The world’s Faustian bargain with these technologies requires payment. There is always somebody downwind.

If there’s anything the Fukushima disaster can teach us, it is that the public should stop tolerating the condescending sneers we’ve heard since the 1950s about the risks of nuclear technologies. Instead, we should demand honesty. Downwinders deserve to be told the truth, and allowed the chance to protect themselves. Governments and corporations must be held to that standard. For our own part, we must open that blind eye we’ve been casting on the dark side of our energy gluttony. Let’s tot up the real cost of doing nuclear business.

Personally, I don’t think that price is worth paying. And anyway, my Chernobyl necklace can’t be pawned. I’m stuck with it.

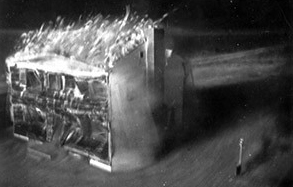

[Photos: Nevada, Spring 1956, Harold Edgerton]

For more Information:

- Poison in the Vadose Zone: An examination of the threats to the Snake River Plain aquifer from the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory.

- United States Nuclear Tests, July 1945 to 31 December 1992. Robert Standish Norris and Thomas B. Cochran.

- The U.S. Atlas of Nuclear Fallout from 1951-1962 Vol. I: Total Fallout, by Richard L. Miller, LEGIS Books, 2002.

- National Cancer Institute: About Radiation Fallout.

- Understanding Radiation: Ionizing & Non-Ionizing Radiation: Health Effects.

- The Low-Use Segment: Idaho’s downwinders got their hearing. But are their voices being heard? By Nicholas Collias, Boise Weekly, November 17, 2004.

- Downwinders’ long journey to justice, by Tona Henderson, Idaho Statesman, April 25, 2010.

- Suffering Effects of 50’s A-Bomb Tests, by Sarah Kershaw, New York Times, September 5, 2004.

- Implications for environmental health of multiple stressors, Mothersill C, Seymour C., J Radiol Prot. 2009 Jun;29(2A):A21-8. Epub, May 19, 2009.

- Ionizing radiation-induced bystander effects, potential targets for modulation of radiotherapy, Rzeszowska-Wolny J, Przybyszewski WM, Widel M., Eur J Pharmacol. December 25, 2009; 625(1-3):156-64. Epub, Oct 14, 2009.

- A Feasibility Study of the Health Consequences to the American Population from Nuclear Weapons Tests Conducted by the United States and Other Nations.

- Chernobyl’s lessons for Japan - New analysis finds elevated thyroid-cancer risk unabated 20 years after the accident, by Janet Raloff, Science News, Web edition: March 17th, 2011.

- Radiation Exposure Compensation Program.

- Individual Dose and Risk Calculator for Nevada Test Site fallout.

- State and County Exposure Levels to I-131.

- Fallout from Nuclear Weapons Tests and Cancer Risks, by Steven L. Simon, André Bouville and Charles E. Land, American Scientist, Volume 94, 2006.